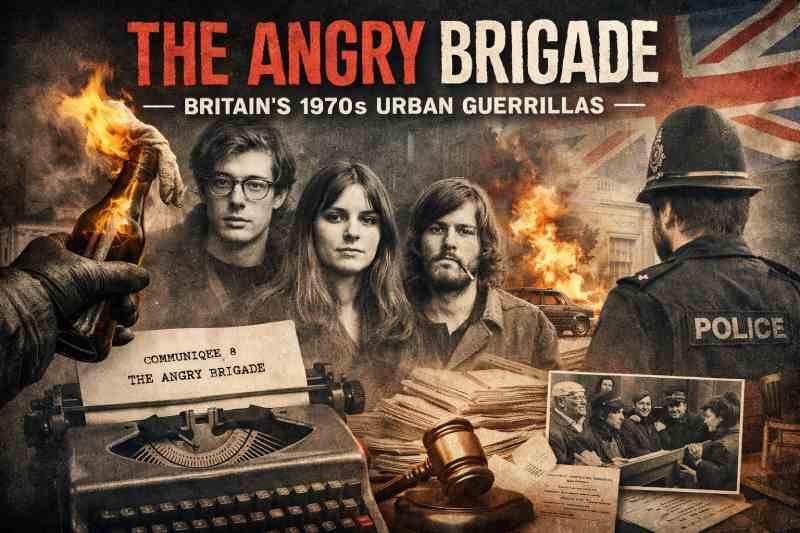

The Angry Brigade: Britain’s Radical Urban Guerrillas of the 1970s

The late 1960s and early 1970s were years of political upheaval in Britain. Student protests, anti-Vietnam War marches, labour unrest and countercultural movements all shaped a restless national mood. Within that turbulent atmosphere emerged The Angry Brigade, a clandestine group that would become one of the most controversial political collectives in modern British history.

Operating primarily between 1970 and 1972, The Angry Brigade carried out a campaign of small-scale bombings directed at symbolic targets across England. Though their actions rarely resulted in injuries, their activities triggered one of the longest and most dramatic criminal trials of the twentieth century. Decades later, historians and commentators still debate their motives, their impact and the extent of their organisation.

The Political Climate of Late 1960s Britain

To understand The Angry Brigade, one must first understand the Britain in which it arose. The country was grappling with rapid social change. Post-war consensus politics appeared to be weakening. The Vietnam War had galvanised a generation of young activists who saw American foreign policy as emblematic of imperial aggression. Student occupations and demonstrations became common, and new radical publications flourished.

The period also saw rising tensions between working-class communities and the political establishment. Economic challenges, unemployment and debates over immigration added to a sense of instability. Radical groups across Europe, including in Germany and Italy, were experimenting with direct action tactics. In this charged environment, it is perhaps unsurprising that a British group would adopt similar methods.

Origins and Formation

The exact composition of The Angry Brigade was never entirely clear, even at the height of the police investigation. The group appeared to operate in loose, decentralised cells rather than as a rigid organisation. Those later accused of membership were often young activists linked to anarchist circles in London.

The collective reportedly drew inspiration from libertarian socialist and anarchist thought. They rejected hierarchical political parties, distrusted parliamentary democracy and sought to challenge what they described as a capitalist and authoritarian state. Their name itself suggested a militant posture, though they were careful in their public statements to distinguish between attacking property and harming people.

Ideology and Motivation

At its core, The Angry Brigade espoused an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist worldview. Communiqués attributed to the group framed their actions as resistance against exploitation, state surveillance and corporate power. They positioned themselves as part of a broader revolutionary struggle, aligning rhetorically with global liberation movements.

Unlike some continental groups that escalated into lethal violence, the British collective maintained that their objective was symbolic disruption. Targets were chosen to send political messages: banks, government buildings, embassies and the homes of prominent Conservative politicians. Their aim, according to their own statements, was to demonstrate that ordinary people could strike back against structures of authority.

However, the line between symbolic protest and criminal violence was sharply drawn by the British public and legal system. Many saw their bombings as acts of terrorism, regardless of intent.

The Bombing Campaign

Between 1970 and 1972, a series of small explosive devices were detonated across London and other parts of England. Police attributed approximately twenty-five incidents to the group. The devices were generally timed to avoid casualties, often exploding at night when buildings were empty.

Notable targets included:

- Commercial premises representing consumer culture

- Government offices and official residences

- The homes of senior Conservative figures

- Military and diplomatic properties

While property damage was significant, injuries were minimal. Only one person was reported to have sustained slight injuries. Nonetheless, the psychological impact was considerable. Media coverage amplified public anxiety, and politicians demanded firm action.

Each attack was frequently followed by a communiqué in which The Angry Brigade explained its motives. These statements were often typed and distributed to newspapers, blending political rhetoric with calls for broader resistance.

The Stoke Newington Arrests

In August 1971, police raided a flat in Stoke Newington, North London. The operation marked a turning point. Several individuals were arrested, and materials allegedly linked to the bombings were seized. The authorities presented the arrests as a decisive breakthrough.

The case culminated in the trial of what became known as the “Stoke Newington Eight”. Proceedings began in May 1972 and lasted until December of the same year. It was, at that time, one of the longest criminal trials in British history.

The Trial and Convictions

The prosecution argued that the defendants were central figures in The Angry Brigade and directly responsible for the bombing campaign. Evidence included forensic material, witness testimony and documents found during police searches.

The defence contended that the case was politically motivated and that the evidence was circumstantial. Supporters outside the courtroom framed the trial as an attack on radical dissent rather than a straightforward criminal prosecution.

Ultimately, four of the eight defendants were convicted and received sentences of ten years’ imprisonment. The others were acquitted. The verdicts did little to settle the debate. For some observers, the convictions demonstrated that the state had successfully dismantled a dangerous conspiracy. For others, the trial raised troubling questions about civil liberties and policing methods.

Public Reaction and Media Portrayal

Public opinion in Britain during the early 1970s was deeply divided. Many citizens viewed The Angry Brigade as reckless extremists who endangered lives and undermined democratic society. Newspapers often described them in dramatic terms, reinforcing a narrative of clandestine menace.

Yet within certain countercultural and radical communities, there was a measure of sympathy. Some activists argued that property damage was a legitimate tactic in the face of what they saw as systemic injustice. The group’s communiqués were circulated and debated in underground publications.

The media spotlight ensured that the name The Angry Brigade became embedded in public consciousness, even among those who knew little of the group’s ideological background.

Comparisons with European Movements

Across Europe, the early 1970s witnessed the emergence of armed revolutionary groups such as the Red Army Faction in Germany and the Red Brigades in Italy. These organisations engaged in kidnappings, assassinations and prolonged campaigns of violence.

Compared with those movements, the British group’s actions were limited in scale and duration. There were no fatalities directly linked to their bombings, and their campaign lasted only a few years. Nevertheless, the comparison contributed to heightened fear. The prospect of Britain experiencing similar levels of political violence alarmed the authorities.

Disbandment and Aftermath

Following the trial and convictions, activity attributed to The Angry Brigade largely ceased. Some commentators have suggested that the arrests effectively dismantled the network. Others believe the group’s loose structure meant that it dissipated rather than formally disbanded.

In later years, former defendants spoke publicly about their experiences. Some maintained their innocence; others reflected critically on the political climate of the era. The story became the subject of documentaries, books and theatrical productions, keeping the narrative alive in cultural memory.

Historical Assessment

Historians continue to debate how to categorise The Angry Brigade. Were they terrorists, radicals pushed to extremes, or misguided idealists responding to a tumultuous time? The answer depends largely on perspective.

From a legal standpoint, the use of explosives against property constituted serious criminal offences. From a historical perspective, the group’s actions must be situated within a broader wave of global protest and radical experimentation.

Importantly, their campaign did not evolve into sustained or mass-casualty violence. This distinction has shaped later assessments, with some scholars viewing them as emblematic of a particular moment rather than as architects of a prolonged insurgency.

Legacy in Contemporary Britain

Today, The Angry Brigade occupies a complex place in British political history. Discussions about protest, direct action and state response often reference their case. In academic circles, the trial is examined as an example of how the justice system handles politically sensitive prosecutions.

Culturally, the group has inspired artistic interpretations that explore themes of idealism, rebellion and the consequences of militancy. For younger generations, their story offers insight into a chapter of history that feels distant yet strangely familiar in its questions about dissent and authority.

The debate over whether dramatic acts of sabotage can ever be justified remains unresolved. What is clear is that The Angry Brigade forced Britain to confront uncomfortable questions about the limits of protest and the meaning of democracy.

FAQs

What was the main aim of The Angry Brigade?

The group claimed their primary aim was to challenge capitalism and state power through symbolic acts of property damage rather than to cause harm to individuals.

How many bombings were linked to The Angry Brigade?

Police attributed roughly twenty-five bombings to the group between 1970 and 1972, mostly targeting buildings and commercial premises.

Did anyone die because of their actions?

No deaths were directly linked to their bombings. Reports indicated only minor injuries in one incident.

What was the Stoke Newington Eight trial?

It was the lengthy 1972 criminal trial of eight individuals accused of involvement in the bombing campaign. Four were convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Why is the group still discussed today?

Historians and commentators examine their actions to understand the political tensions of the era and to explore wider debates about protest, extremism and civil liberties.

Conclusion

The story of The Angry Brigade is inseparable from the volatile spirit of early 1970s Britain. Emerging from a climate of protest and ideological ferment, they chose a path of clandestine sabotage that shocked the nation and tested the limits of tolerance for radical dissent.

Although their campaign was short-lived and comparatively restrained when set against some European counterparts, the impact was profound. The arrests, trial and convictions marked a defining moment in the relationship between the British state and revolutionary activism.